‘Be not solitary, be not idle’: secrets of 400-year-old self-help book unlocked

‘Be not solitary, be not idle’: secrets of 400-year-old self-help book unlockedon Jun 28, 2021

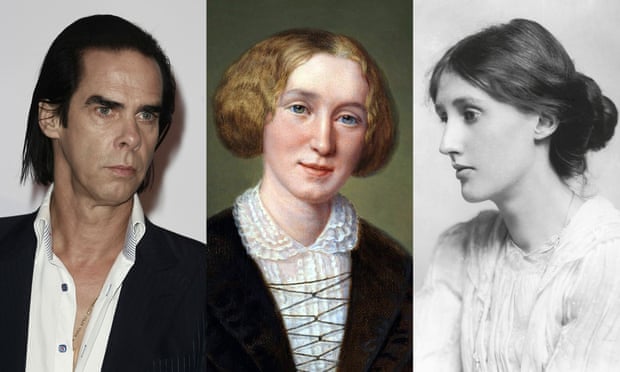

Admired by everyone from John Milton to Nick Cave, The Anatomy of Melancholy has always been a text that has dazzled and confounded its readers in equal measure.

Now, exactly 400 years after it was published, an academic has painstakingly traced the meaning of thousands of its sphinxlike allusions, enigmatic references and arcane quotations, allowing Robert Burton’s famous text to be fully understood for the very first time.

Dr Angus Gowland of University College London told the Observer there are now only nine known mysteries and riddles of the text left to solve.

In total, Burton used more than 13,000 quotations and references in his book to discuss the causes and symptoms of melancholy – a term that in 1621 covered “a catch-all category of anything that’s gone wrong with your mind” – and to explain the various physical, philosophical and emotional remedies his readers should use as cures.

In some ways, the text is like “an early modern self-help book”, said Gowland. “The idea is that when you read this, you’ll come across parts – Burton says – you will recognise. And when you see something about yourself, that’s when he thinks you should pay attention and implement the kind of remedies being presented. There’s a kind of therapeutic aspect to the text, a pre-modern notion of self-knowledge.”

Over the centuries its legion of admirers has included literary figures such as Samuel Johnson, John Keats, George Eliot, Virginia Woolf and, more recently, Philip Pullman. “One of the reasons it has appealed to people is because it is not about a particular disease, but about any condition of irrationality or strong and destructive emotions. And it presents ways of thinking about these conditions that are not just medical, but also moral and spiritual,” he said.

Despite its notoriety as a groundbreaking work, some of the quotations, statements and references in the work have long baffled readers. Gowland has spent the past 10 years unravelling most of these. Their meanings will be revealed when a new Penguin Classics edition of the text, edited by Gowland, is published on 1 July

“The purpose of the edition is to make it accessible, not just to scholars, but to the general reader who is interested in this kind of book,” Gowland said. “All the obscure terms and archaic and obsolete language has been glossed systematically for the first time, to allow you to read and understand Burton’s words properly, as they were originally intended.”

For example, scholars have typically claimed that Burton and his contemporaries believed melancholy was caused internally by black bile in the human body. But Gowland reveals that the vocabulary employed by Burton – particularly his use of the word “artificial” – indicates that, importantly, Burton also thought melancholy was caused by factors external to the body, and that every living organism was susceptible to it.

Similarly, Burton describes the “malady of melancholy” as an “ill habit”. This has typically been misunderstood by scholars and readers, Gowland said, because the term “habit”’ used to have a technical sense when applied to the physical body. “When Burton uses it, it means ‘physical condition or constitution’. This is essential for the literal understanding of the text in various places,” he said.

Other riddles that have now been solved include what Burton meant when he cryptically advised his readers: “Don’t crush the basil.” “Previously, scholars thought it meant ‘don’t make scorpions’. But why would you say that?” Gowland traced the phrase to a Latin saying published in an obscure text in 1590 and discovered what Burton actually meant was: “Be gentle with yourself – or with others.”

“There are loads of examples where the text was there, people read it and no one knew what it meant,” added Gowland. It’s possible this was deliberate. “One way of making sense of all the unattributed quotations and obscure allusions is to see them as puzzles left by Burton for his readers and for posterity. He likes to play games with his readers.”

Whatever type of melancholy a reader is suffering from, whether it is a broken heart, religious superstition, a bereavement, serious depression or anything that would now be viewed as a mood disorder, there is a remedy in the book for it.

Gowland hopes the new 1,376-page edition will open up the masterpiece to new readers, but also satisfy the yearnings of existing enthusiasts, who surprised publishers in recent years by ensuring earlier reprints sold “extremely well”. “The number of emails I’ve had from people, who love the book, asking when it’s coming out and getting impatient… It’s got this random fanbase of people who really love it,” he said.

Many of the remedies for melancholy discussed in the book – from the importance of talking to friends, to the health benefits of taking scented baths – are coming back into fashion, especially following the isolation of recent lockdowns and restrictions on socialising.

“There’s a resonance with what’s happening today, because solitude is a condition which melancholy follows like a shadow.” In fact, Burton viewed melancholy as a pathology of solitude. “His last words that aren’t a quotation in the book are: Be not solitary, be not idle.”

Source - The Guardian

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.